Monumental Questions - What is the Significance of the California Condor to Native Californians

Recently Tuleyome shared the Monumental news that Molok Luyuk, or Condor Ridge, was added to the boundaries of the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument. This culturally and biologically significant addition was historically California Condor habitat.

Most of us are probably familiar with the life history of the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus). Specifically how they once soared over much of North America witnessing the end of the wooly mammoths, mastodons, saber tooth tigers and giant sloths. They coexisted with America’s first people, saw the arrival of the Spanish and the British and later experienced the Gold Rush era and the havoc that came with it. By the 1900’s the population was in drastic decline and by the late 1940’s, California Condors were already rare. In 1982, only 22 California Condors survived worldwide and by 1987, they were extinct in the wild with the carefully deliberated capture of the remaining surviving 22 birds to begin a captive breeding program. By 2004 the total population (captive and free flying) numbered in the 500’s. Today the population remains roughly the same and has not declined. Since the beginning of the captive breeding program, California Condors have been reintroduced into the mountains of Arizona, Utah, Baja California and central and southern California. Part of the reason for the slow population growth is that California Condors do not reach sexual maturity until six years of age but may not breed until they are seven or eight years old and lay only one egg every other year. On top of their perhaps unfortunate biology, the use of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) resulted in dramatically thinner egg shells in many species of birds causing them to break while being incubated by the parents and kill the developing baby bird. And in addition to all of these concerns, California Condors were extraneous victims of lead poisoning and trophy hunting.

Native Californians were enthralled with the California Condor’s impressive size and appearance. California Condors are the largest flying bird in North America with a wing span of nearly ten feet (that’s the distance of the rim of an NBA basketball hoop to the floor). Full grown adults can weigh up to 30 pounds and if not subject to lead poisoning and Avian Flu can live for roughly 50 to 60 years in captivity.

Throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, researchers have found evidence that the California Condor helped form Native American’s mein of worship, spiritual beliefs, ceremonies, songs, dances and legends. In Oregon, the remains of over 60 birds were found at a site called Fivemile Rapids near what is currently called The Dalles. Some of the birds’ remains were intact while others appeared to have been used for other purposes including feather plucking. In the Bay and Delta regions of California, archeological sites have yielded a substantial amount of California Condor bones. Some of the wing bones were delicately engraved and made into flutes and other remains were found with human burials. Another location near Berkeley revealed what appeared to be a ritual condor burial site and still another site near Sacramento contained the remains of a cape made from California Condor skin and feathers.

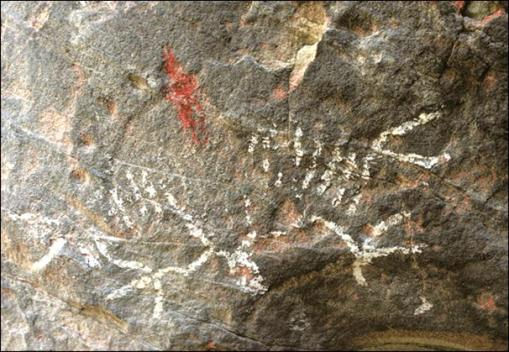

There are at least 65 different known tribal names for the California Condor. Cultural significance is found in not only tangible discoveries such as capes and skirts made of skin and feathers, headdresses made of condor and Golden Eagles feathers, bone flutes, and cave art but the California Condor has also been immortalized in oral legends passed down from generation to generation. The condor had many roles including sorcerer, messenger, kidnapper, robber, gambler and killer. The Chumash have a story in which they believed that the condor was an all white bird but when it saw fire for the first time it was curious and flew too close to the flames singing all of its feathers except for the white under its wings where it didn’t touch the fire. Another tribe believed that the condor was an all black bird but their sky god shot light into the condor and it exited through its wings and that’s why part of the underwing remains white. Another tribe believed that condors removed foulness from the Earth which is scientifically true since they are obligate scavengers and help get rid of carrion. The Pima believe that condors created thunder and flashed lightning from their red eyes.

The California Condor has a cultural celestial presence as well. The constellation we call Cassiopia is called Condor by the Chumash. Many Native Americans believe that Condor held up the upper world with its wing and is responsible for solar and lunar eclipses.

It was believed that condors could infuse humans with supernatural powers. Central Miwok shaman believed that they could acquire powers that would allow them to become finders of lost objects, read minds, heal the sick and obtain anything they wanted. Money finders of the Yukuts and Western Mono tribes wore full length coats made of condor feathers and could find misplaced valuables. The Condor shaman of the Chumash tribe was believed to be able to locate missing people using the supernatural powers given to him by Condor. There are many other stories about the condor’s ability to heal the sick just by flying over them. They also believed that they could pull sickness from an individual by putting primary and secondary (the big ones) wing feathers down a sick individual’s throat and pulling out the illness with the feather.

The California Condor is the most powerful bird in Native American culture but there are few relics remaining today. This is partly because they believed that when a chief or shaman died, their condor feathers went with them. It’s been said that the Gold Rush was the genesis of the California Condors’ near extinction. They were shot for sport and captured for curiosity. Many died miserable deaths either starving in captivity or becoming a victim of lead poisoning as a result of eating discarded carcasses shot with lead shot. They were harvested and killed for their flight feathers as the quills were used to store gold dust. Sadly, California Condors escaped extinction only to later face man.

The Yurok tribe, the National Park Service and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service have partnered to form the Northern California Condor Restoration Program in a collaborative effort to reintroduce captive-bred condors to Yurok Ancestral Territory and the Pacific Northwest. To date, eight birds have been released and are flourishing in their new home. John W. Foster, a retired senior California archeologist wrote, “It is apparent that California Condors held a special place in the lives and ceremonies of California natives. It was a revered creature, a master of the spirit, who gave power to humans for a variety of world renewal and cosmic purposes. It is associated with death and mourning as well as rebirth and renewal.” Hopefully one day soon we will see California Condors again soaring over Molok Luyuk.

-Kristie Ehrhardt (kehrhardt@tuleyome.org)

Tuleyome Land Conservation Program Manager

RECENT ARTICLES